Wonderwall Music

18 February 2020

by Matt Hurwitz

Just as The Beatles were putting the finishing touches on their film, “Magical Mystery Tour,” for broadcast at the end of 1967, George Harrison was beginning his own new project – creating the music score for “Wonderwall,” a movie by indie director and friend, Joe Massot.

“’Wonderwall’ was a kind of 60s hippie movie,” George said. “Joe Massot came to me and asked if I would do the music to his film. I told him, ‘I don’t do music to films,’ and he said, ‘Well, whatever you give me, I’ll have it.’”

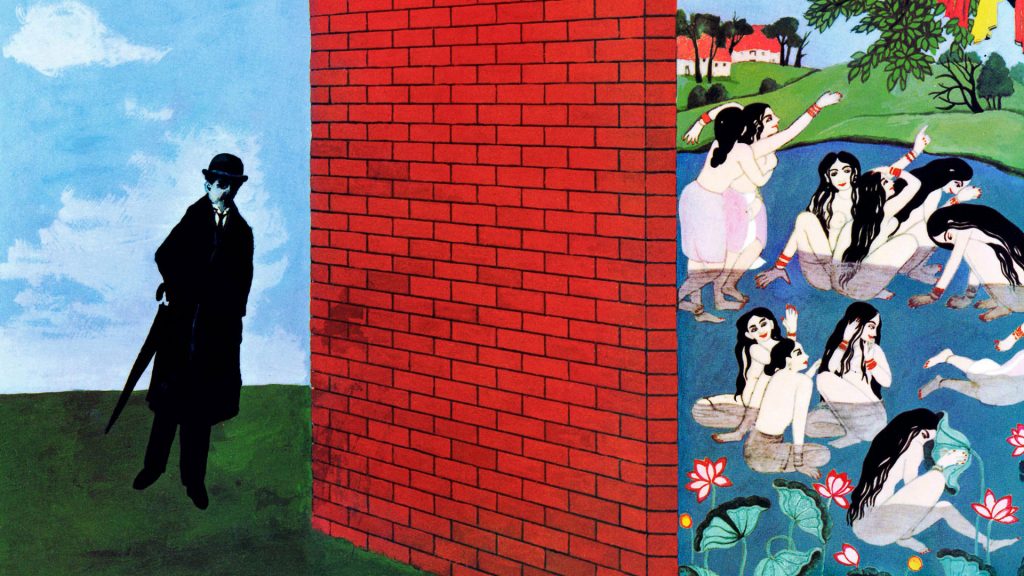

The film was about a lonely professor (Jack MacGowran) in a cheap apartment who spends his time watching through a hole in the wall the goings-on in the unit next door, inhabited by a young photographer and his model girlfriend (Jane Birkin), with whom he develops an obsession. Plentiful with the psychedelia of its day, there was ample opportunity for George to fill it with whatever musical whimsy he chose. “He was free to do absolutely whatever he liked,” says friend and arranger John Barham.

What George liked, as fans had been discovering, was Indian music. “Indian music was big at the time in London,” recalls drummer Roy Dyke, whose band, The Remo Four, provided the backing for the western-themed pieces on the soundtrack. “Everybody was wearing Indian clothes. And George was really into Indian sounds and wanted to turn a lot of people onto it.” Adds George,

“I thought, ‘I’ll give them an Indian music anthology, and, who knows, maybe a few hippies will get turned on to Indian music.’ ”

As any film composer would do, the first step George took was what would today be called a “spotting session.” Visiting Massot and editor Rusty Coppelman at Twickenham Studios, he watched a rough cut of the film several times, taking detailed notes about the story and scenes and deciding the type of music appropriate for each.

He eventually compiled a list of about an hour’s worth of music cues, with precise timings required for each. George then spent much of November and early December recording rough outlines of musical ideas and themes, recording a few titles (whose names would change), “India” and “Swordfencing,” at Abbey Road on November 22 and 23. [For those keeping their Beatle calendar, “Hello Goodbye” was released the following day.]

Wonderwall Tape Box

While in prep, George made a few important contacts. Among the first was John Barham, who met George in 1966 while working as an assistant to Ravi Shankar. “Ravi took me down to George’s house in Esher, where he had asked Ravi to play a recital for a small gathering,” Barham recalls. “A few months before recording began on Wonderwall, he asked me if I wanted to do some arranging, and so of course I agreed,” beginning a relationship that would span years.

The first true sessions for the film/album took place at De Lane Lea Studios in London on December 21. Those recordings featured just two players – sarod master Aashish Khan and his longtime tabla player, Mahapurush Misra, who were experiencing their first winter together on tour in England. George had met Khan the year before in Varanasi, India, shortly after George began studying with Ravi, and the two became good friends. “I was in England with my father,” the late sarod player Ali Akbhar Khan, “and George came to my hotel and asked if I would be interested in playing for his movie, Wonderwall. So the next day he took me to the studio, and I recorded with Mahapurush.”

The sarod is somewhat like a sitar, though without frets, held in the lap while playing. Its 25 strings are plucked, like a lute, with a pick made of coconut shell, while the player uses both a well-tuned ear and a fingernail on the other hand, used like a slide, to find notes.

Khan and Misra played together on two tracks, Misra playing alone on “Tabla and Pakavaj,” the latter a double-ended drum laid sideways and played with both hands.

For “Love Scene,” where Prof. Collins watches as the girl and her boyfriend. . . do the obvious, Barham recalls, “George said, ‘Oh, we need romantic music here.’ I knew a raga which had been created by Aashish’s grandfather, Allauddin Khan, called ‘Mauj-Khamaj,’ which I always thought was very romantic. So I suggested that to Aashish.”

Khan recorded several passes, and then George asked him to do something commonplace in his own pop recording, though unusual for an Indian musician – double-track himself. “He said, ‘Why don’t you play something along with it?’” the musician remembers. “At first I was very confused, but then I started listening and found some spaces in between and started filling them, and he liked it very much.”

The other piece, “Gat Kirwani,” used over a modeling sequence, is based on another raag, “Raga Kirwani,” made popular around that time by Allaudin Khan and Shankar, which George requested Khan play.

The following day, George did the first of a number of sessions with a group he had known from Liverpool, The Remo Four – Tony Ashton (keyboards), Colin Manley (guitar), Phil Rogers (bass) and Roy Dyke (drums). The quartet, recording at Abbey Road, and played on nearly all of the western music tracks, typically by themselves, with only occasional overdubs added by George or Barham. The group – also NEMS artists, like The Beatles – had just returned from a stay at the Star Club in Hamburg, the legendary Beatles haunt, and were looking for their next gig, so George asked their help.

The process was straightforward in coming up with the unique music for the cues. “We would sit in a circle and listen to George explaining what he wanted, sometimes on a guitar,” Dyke recalls. “Then we’d jam a little bit, come up with something, and he’d say, ‘Yeah, I like that,’ and we’d record. It was all improvised, nothing written down, all very quick. And it was such a warm atmosphere.” The group recorded on this date with engineer Pete Bown, as well as in late January with Ken Scott recording.

Ashton handled nearly all of Wonderwall’s keyboards, including a Mellotron, still a fairly new instrument at the time, and heard throughout the album. “George had all kinds of instruments there,” Dyke says. “Tony was a good keyboard player, particularly organ. When I met him in 1962, the groups were beginning to change from all guitar to guitar and keyboard. He was a solid musician.”

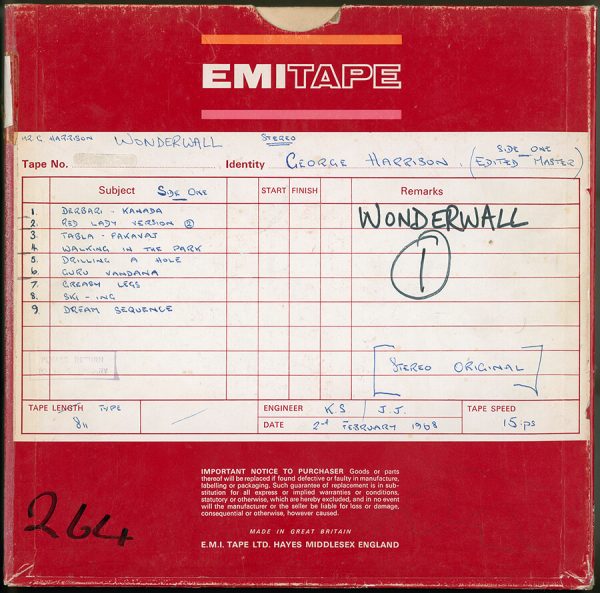

On “Red Lady Too,” the second (thus “Too”) of two cues where Collins observes the girl bathed in red light, Ashton plays a melodic tack piano, joined on the recording by Barham on a piano bass. [The other “Red Lady” cue, seen first in the film, as well as at the end, where Collins finds the girl on her red bed, after attempting a suicide by overdose, received a new title, “Wonderwall is Here,” prior to release. Also, as seen in the Side 2 LP master tape box in the CD booklet, “On the Bed” appears to have been confused with its original title, “Piano and Trumpet,” with the running order intending to have been changed, though that never occurred. “Glass Box,” which plays over an argument between the girl and her boyfriend, replaced “Waterworks Dream,” which follows that sequence in the movie. “Vocal, Flute and Organ,” heard as the film closes, was given a somewhat less on-the-nose title, “Singing Om.”]

On the jovial and quirky “Drilling a Home,” as Collins mangles his flat with various tools, Ashton puts the Mellotron through its paces, providing the banjo, drums and even a cheesy trumpet. [The Monkees’ Peter Tork is known to have played banjo on one cue, though not this one.] The celli, organs and flute on “Greasy Legs,” heard as the girl dances with a female friend, are similarly provided by the Mellotron, which makes use of tape strips inside with samples of various instruments (It is most familiar to Beatles fans for the “flute” heard at the beginning of “Strawberry Fields Forever”).

“Dream Scene” combines a concoction of Indian music and voice (which George borrowed from Abbey Road’s library collection) and other instruments. John Barham actually recorded his first contribution on this track – a flugelhorn. “There was a flugelhorn of Paul McCartney’s lying around the studio,” he recounts. “I just happened to mention to George I had been a trumpet player six years prior. So he said, ‘Would you want to do something?’ So I warmed up for about an hour in another studio and then overdubbed it.” He did so again on “On the Bed,” which features a piano from George himself, who also played a sitar-like guitar part, based on a theme Barham had created a few days earlier.

“Dream Scene,” as well as “Cowboy Music,” feature a chromatic harmonica played by studio veteran Tommy Reilly, who was in his 60s at the time. For the latter track (heard as the boyfriend sits atop a rocking horse while making a date with another woman), Harrison asked the Remos for a “classic Hollywood western theme,” complete with authentic-sounding horse clops, made by Dyke with a pair of wood blocks.

A couple of players featured on no other track dropped in just after New Year’s, on January 2 and 3, to record the psychedelic rocker, “Ski-ing.” “That’s Eric Clapton and Ringo,” Barham says of the two, sometimes credited herewith as “Eddie Clayton” and “Richie Snares.” Clapton double-tracked himself, to fill out the band. [As seen in the original Side 1 LP master in the George Harrison: The Apple Years box set book, “Ski-ing” and ‘Gat Kirwani” were originally to appear as a single track]

Wonderwall Tape Box

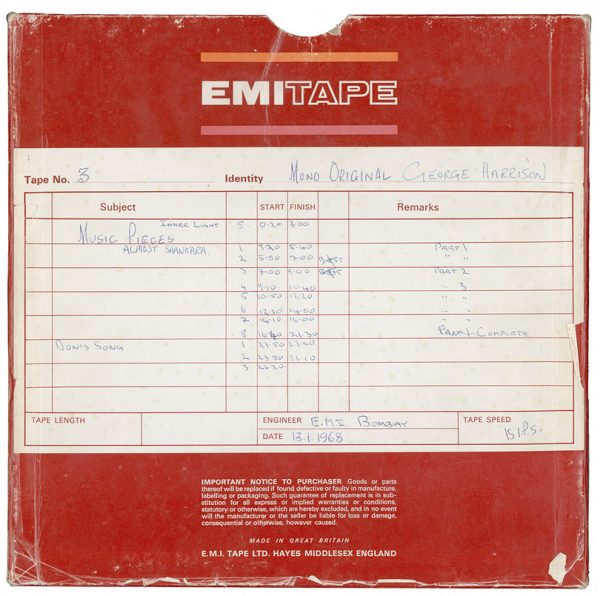

For the Indian music recordings, George decided to go where Indian musicians were plentiful – Bombay. EMI/HMV had six recording studios in India, but EMI Bombay was considered the country’s recording hub, due to the presence of the film industry there. Recording took place from January 9 thru 14, each day from 11am to 8 or 10pm, engineered by a team of three staff engineers, including J.P. Sen and another by the name of Matgaonkar.

The studio, located in an insurance office building near the Indira Docks where the label also kept its record stock, featured a large mono EMI BTR2 tape machine in Studio 1, where George was to work. “Mr. Bhaskar Menon brought a two-track machine all the way from Calcutta on the train for me,” George recalled, “because all they had in Bombay at the time was a mono machine, the same kind we used in Abbey Road to do the ‘Paperback writer writer’ echo.” Some recordings were indeed made in mono, with others in stereo.

Harrison contacted sitar player Shambhu Das, a disciple of Ravi Shankar’s whom George met during his first visit to India for lessons. “George called me directly from London and asked me to help with these recordings,” Das says. He then gave Das a list of instruments he intended to use. It was then up to HMV Bombay’s head of A & R, Vijay Dubey, to find musicians to play them.

“George had a serious musician’s ear for recognizing a number of major Indian instruments, largely as a result of his education by Ravi Shankar,” notes Menon, then chairman of EMI India, and later head of Capitol in the U.S., and himself a protégé of George Martin.

The process in India differed slightly from that in London. After breakfast, George would arrive at the studio, where he was then treated to sample playing of whichever musicians Dubey had brought for the day. “In the evening, George would return to the Taj Mahal, where we were staying, and spend his time making notes about the instrument he had heard and the sounds they were capable of making,” Menon recalls. “He was an incredibly hard worker and took this very seriously. It was a kind of immersion for him into the folk music of India.”

The next day, Harrison would meet with the musicians, again sometimes with a guitar, sometimes simply humming tunes, to convey the musical concepts he sought from them. “Most of them didn’t speak a word of English, so he had to depend on his ‘HMV friends,’” Menon says. “But mostly it was just musicians communicating, which was marvelous to watch. They would play a little bit of something, he would say, ‘No, no, no – like this,’ and then they would record.”

Recalls Das, “George would convey to me what mood he needed, and the musicians improvised, and then he okayed for the recording.”

One of the first instruments George became enamored of was the shehnai, an oboe-like double-reed instrument historically used to herald the arrival of both bridegrooms and Maharajas. “They would play atop a stage on top of the gate to the palace, helping create a big entrance,” Aashish Khan explains. The instrument is featured prominently on Wonderwall, played by Sharad Kumar and Hanuman Jadev, greeting the listener on the opening track, “Microbes” (originally titled Darbari-Kanada, after a Hindu raga on which it is loosely based).

Another oft-featured instrument is the taar-shehnai, played with a bow, like a western string instrument, played by Vinayek Vora. “It is actually an esraj,” Khan explains, “but with a gramophone-like horn hooked onto the first string to give it a nasal sound,” much like the shehnai itself. It is heard on several pieces here, most notably making the “crying” sounds on. . . “Crying.”

L-R: Vinayek Vora (playing a taar-shehnai), Shambhu Das (holding stopwatch), unknown engineer, George, unknown (Rijram Desad’s assistant), Rijram Desad (at harmonium)

Other string instruments included the sitar (played by Das and Indril Bhattacharya), and the surbahar, which is like a sitar, but pitched lower, played by one of its masters, Chandrashekhar Naringrekar.

The beautiful dulcimer-like santoor, its 116 strings played with walnut sticks, was performed by Shivkumar Sharma. It is most visible on “In the Park,” alongside the tabla tarang, a set of seven tuned tablas, played by Rijram Desad, who can also be heard playing the harmonium.

George made good use of his time, wrapping up early enough to make additional recordings of other ragas for possible Beatle use – two of which appear as bonus tracks on the CD reissue, “Almost Shankara” and another, which would become “The Inner Light.” Recorded on January 12 over four takes (with a fifth the following day), the recording features (along with likely players): a harmonium (Desad), taar-shehnai (Vora), sitar (Das), a dholak (a two-headed drum, like the pakavaj) (Desad or Ghosh), flute (S.R. Kenkare, Hari Prasad Chaurasia), and a bul-bul tarang (player unknown, but perhaps Das or Bhattacharya). The latter is the song’s signature plucked string instrument, played by depressing keys, like on a table harp, and picking strings with the other. Again, as Bhaskar Menon described, one can clearly hear George communicating with the musicians as only musicians do, gently guiding them with his ideas.

Upon his return to the UK, George went back to Abbey Road for additional recording with The Remo Four and Ken Scott, taking place on January 17, 22, 26, 30 and 31. On the 22nd, George produced five takes of a song of the band’s called “In the First Place,” with Tony Ashton singing. The track lay unknown until 1998, when Joe Massot created a new director’s cut of the film, asking George for access to additional session material, including the song (Massot used the song over the opening titles in his new cut of the film). With the completion of those recordings, the soundtrack was complete – the album was mixed by Harrison and Scott on February 1 and 2.

For the front cover, George contacted Bob Gill, a popular designer in London. “I came to The Beatles’ office on Savile Row, and the four of them told me how important this project was, because it was the first album on their new label, Apple,” Gill recalls. “They explained what the movie was about, so I thought it would be fun to erect a barrier, a brick wall, which divided the sleeve in half. Then I put a boring man in a gray suit and bowler hat on one side, and on the other a typical Indian miniature,” with tempting ladies bathing in a pond. Gill’s original design featured a solid brick wall, from which George then requested a single brick removed, to reflect the professor’s own predicament.

For the back cover, George produced a favorite photo recently taken by one of The Beatles’ oldest friends, Astrid Kirchherr (then Astrid Kemp). The back cover was laid out with the photo and credits by an up-and-coming Alan Aldridge, then one of Gill’s students, but the design was later relegated to placement as an album insert, in favor of a powerful agency photo of the Berlin Wall.

Wonderwall Music by George Harrison was released on November 1 in the UK (December 2 in the U.S.), making it the first album released on the Apple label, as well as the first true solo album by a Beatle. For George Harrison, it was just the beginning.

Matt Hurwitz

Read the full story behind the Wonderwall Music album in uDiscover Music’s ‘Behind The Albums’ series.